We touched on this in chapter one, but it bears repeating: assisting veterans and their families costs cold hard cash, and there is a constant fight for veterans’ fair share of federal, state, and philanthropic dollars. Just as we fund bullets and boots, so should we fund the enduring costs of war and military service.

The budgets for the Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) are separate, and the VA, despite being the second largest federal agency and the largest healthcare system, must have its budget re-authorized yearly. This is all woefully inefficient, but it is the system we find ourselves negotiating.

And because most care is delivered in communities, and less than half of veterans access the VA, much of the cost of war is externalized to localities and individuals. Yet the “sea of goodwill” has begun to dry, and veterans represent a very small portion of philanthropic giving and of funder portfolios.

FEDERAL, STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT FUNDING

Congress authorizes and appropriates the VA’s budget to deliver health services, compensation and disability, educational and other benefits, and cemetery services. Local community-based agencies may be funded by the VA to administer housing programs (Grant and Per Diem), eviction prevention (through Supportive Services for Veterans and Families; SSVF), and employment and training (Homeless Veteran Reintegration Program).

States may fund local veteran programs through a variety of means: for example, through distribution of federal block grants funding, such Department of Labor (DOL) dollars. States also may also independently fund community-based veteran care; most notably county veteran services offices (CVSOs), which help secure VA benefits and other resources.

Community-based nonprofits are best equipped to deliver local services, and federal funding provides core resources not only to deliver services but to leverage with other sources of income in order to provide wraparound care. Systems of government funding are by no means sufficient—they can be burdensome in their rigidity, provide less funding than is necessary, offer very low overhead, and simply cannot anticipate the varied nature of every community need. Agencies need both unrestricted funds to fill gaps and maintain agility in real-time changes in need. The machine will not run without this oil.

It is beyond the scope of this guide to delve into individual state means of funding local government and private nonprofit community-based agencies. That said, advocates should encourage state leaders to reach beyond the traditional “veteran” funding and ensure that veterans get their fair share of aging, mental health, education, and other state-administered funds.

THE PHILANTHROPIC WORLD: FOUNDATION AND INDIVIDUAL SUPPORT

Private and corporate philanthropy dedicated to veteran care is miniscule. The harsh truth is that less than two-tenths of one percent of all charitable giving is directed to military and veteran agencies.

A figure bandied about states that there over 40,000 nonprofit charities whose mission is to serve service members, veterans, and their families. This number is highly misleading; almost 80 percent, or 33,347 of those 42,035 nonprofits counted are local posts of veterans organizations such as Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion. These individual posts serve a vital purpose for their local communities, members, and their local veterans, but generally do not provide health and social services.

Just 3,035 of the 42,035 nonprofit organizations cited may have staff or provide a consistent array of services such as housing, employment and training, legal assistance, or health and social services.

Further still, much of the spike in foundation giving in the mid-to-late-2000s until present is focused solely on post-9/11 veterans. Certainly, these veterans need services, and assistance provided during transition may prevent the long-term suffering we see among our older veterans. But post-9/11 veterans present a fraction of the total veteran population and there is no reason to limit care to this population. Indeed, choosing not to fund services for veterans of all eras deepens the wounds endured through decades of neglect and furthers the long-term health consequences so present in older veterans.

Veteran services and advocacy too often fall into limbo. Relying on a tiny minority of foundations that list veterans amid their program areas is troublesome given the trickled-down support given to veterans in recent years, yet many funders fail to recognize veterans in funding portfolios dedicated to populations and issue areas that include veterans. Foundations that fund education, aging populations, women, LGBTQ+, healthcare, and criminal justice for example, do not explicitly recognize or distribute grants for veteran projects.

CREATE RELATIONSHIPS WITH FUNDERS

Program sustainability for nonprofits can seem like it begins and ends with funders. As nonprofits continually plan for sustainability, they must seek funding that aligns with their program goals. Sustainable nonprofit organizations, whether large or small, raise funds from a variety of institutional grant makers such as private foundations, corporations, and government agencies.

Funding is not only about a good program and a well-written proposal; it is about creating a relationship with potential and current funders. Initiating, developing, and cultivating relationships with grant makers at an individual level is a critical important step to sustainability.

Figure out who the program officer is and get to know them. Conduct meetings with current and potential grant makers about your organization, the success of your program (with data to back it up), and your understanding of the nature and scale of the problem that you address through your work. Convey the findings of your work in a translatable way that the funder can identify with. Long-term commitments are often gauged when a strong relationship with your program officer is made.

- Call to check-in or notify your program officer of something exciting, whether it be an event, a breakthrough with a veteran, a new and exciting training program, etc.

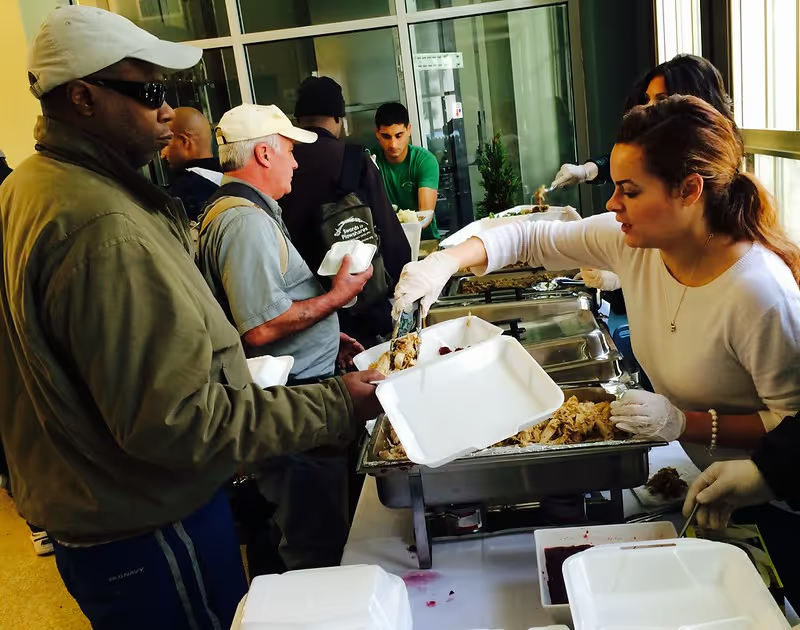

- Invite funders to visit your site for a tour. Make sure key members of your staff are available to talk about your programs. Prepare them with talking points prior to the meeting.

- Do not miss established reporting deadlines! Make sure you write down important reporting dates and notify the funder that you are working on the report before the approaching deadline.

- Establish meetings with funders before and after your reports are due to discuss your findings and answer any questions they may have so they can better understand the workings of your programs.

- Establish measurable, definable goals before you solicit funding. Make sure that these goals are well within your program’s reach—do not over-inflate.

- If you will not meet these goals, contact your program officer prior to submitting your progress report to discuss and be honest about why the goals were not met, and how, if appropriate, methods and goals may be altered to meet veteran needs. It could be the difference between additional funding and never being funded again.

- Be honest with your funder about your challenges. It is not all about success, it is also about learning. Every challenge we experience should be communicated to funders so that they can examine the priorities as they pertain to the needs on the ground and in the communities we serve. Remember, funders do not have firsthand knowledge of direct services and needs of veterans, they rely on their grantees to educate them. Be honest about challenges and what needs are not being met by current funding.